Early in your career as an animator, you'll likely learn a hard truth—sometimes the painful way: doing great work is only half the job, sharing it clearly is the other half. You might remember a short film project where the animation itself was solid, but the review process was pure chaos. QuickTimes flying back and forth over email, files named things like shot_final_v3_really_final.mov, and no one is quite sure which notes apply to which version. Clients were confused, supervisors were frustrated, and you were spending more time managing files than animating.

Fast forward a few years, and tools like Kitsu playlists completely change how studios review animation.

They give you structure, traceability, and a clean way to present work. You can group shots, track versions, and centralize feedback. For most teams, that alone is a huge win.

But here's the thing you learn after years in production: no two studios or clients share the exact same review workflow. Sometimes you need to send assets offline. Sometimes a client wants everything neatly packaged by sequence. Sometimes legal or security constraints mean you can't give direct Kitsu access. In those cases, you still want to leverage Kitsu's strengths without being locked into a single way of sharing.

That's exactly what this article is about.

By the end, you'll know how to create a Kitsu playlist, extract its data with Python, download all related assets in a clean folder structure, and compress everything for easy sharing. This approach can save you hours on real productions and make reviews smoother for both artists and clients.

Let's break it down step by step.

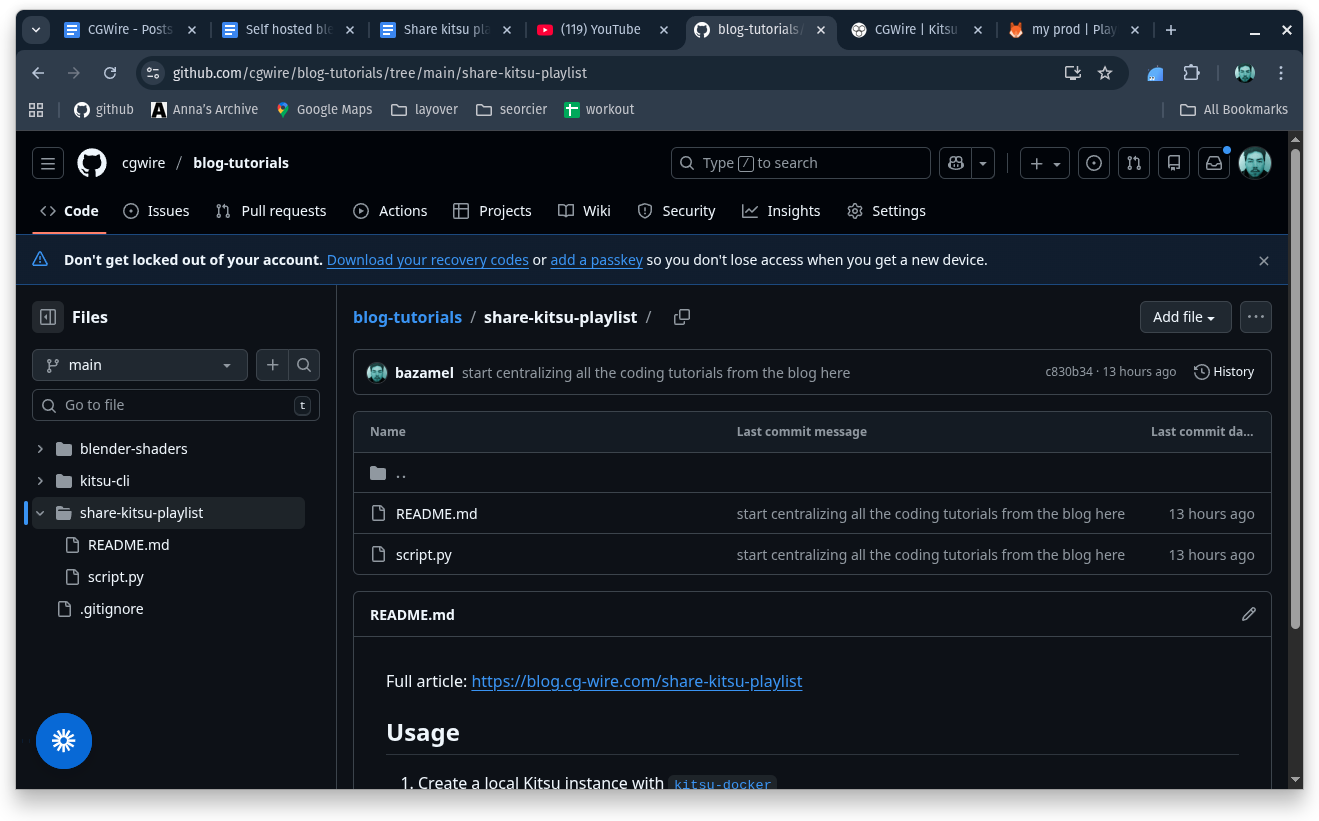

You can find the complete source code for the example integration showcased in this guide on our GitHub:

🔗 https://github.com/cgwire/blog-tutorials/tree/main/share-kitsu-playlist

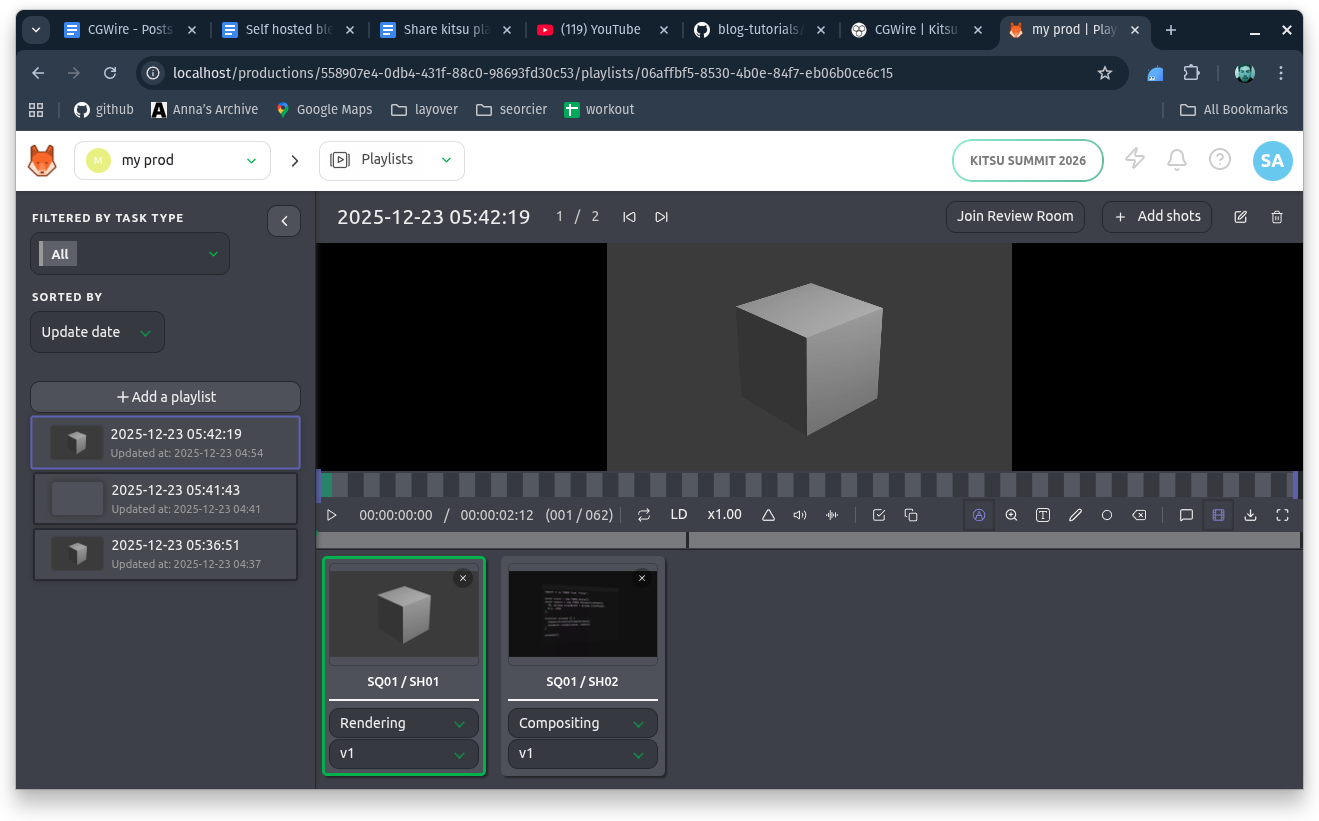

1. Create a Kitsu Playlist

Every solid review workflow starts with a clear intention: what exactly do you want feedback on? Kitsu playlists are built for that purpose.

Creating a playlist from the Kitsu dashboard is straightforward. Navigate to your project, head into the Shots or Assets section, and start selecting the items you want reviewed. It helps to think of playlists as review narratives. Instead of dumping everything in, ask yourself:

- Is this a blocking review?

- Is this a polishing pass?

- Is this focused on animation, lighting, or comp?

For example, on a short cinematic project, you might create separate playlists for:

- "Animation Blocking – Act 1"

- "Facial Polish – Key Shots"

- "Final Lighting Review"

That small bit of organization can make client reviews dramatically more focused.

In Kitsu, once your shots are selected, you can create a new playlist, name it clearly, and order the shots in a way that tells a story. Order matters more than people think. When a client presses play, they can judge the art, timing, and revisions in one place.

2. Get the Playlist Data

Now that we have a playlist ready, it's time to code.

We start by authenticating with Kitsu using the Gazu API client:

import gazu

gazu.set_host("http://localhost/api")

gazu.log_in("admin@example.com", "mysecretpassword")

We can then query Kitsu for available projects and present them in the terminal. The user selects a project, and that choice defines the scope of everything that follows. Because projects are fetched dynamically, the script works across productions without modification:

productions = gazu.project.all_projects()

for i, p in enumerate(productions):

print(f"[{i}] {p['name']}")

production = productions[int(input("Select project: "))]

From there, playlists are queried from the selected project and shown the same way. When a playlist is chosen, the script retrieves the full playlist object from the API.

playlists = gazu.playlist.all_playlists_for_project(production)

for i, pl in enumerate(playlists):

print(f"[{i}] {pl['name']}")

playlist = gazu.playlist.get_playlist(playlists[int(input("Select playlist: "))])

playlist contains the full editorial selection reference: shots, versions, ordering, and linked files are all accessible through this object.

3. Download Related Assets

The next step is turning the playlist data into something reviewable on disk.

The output is a folder hierarchy that mirrors production reality: playlist at the top, sequences underneath, shots inside those, and the actual media sitting where anyone expects to find it.

Playlist_Name/

└── Seq_010/

├── Shot_010_001/

│ ├── anim_v003.mov

│ └── anim_v003.png

└── Shot_010_002/

└── Seq_020/

└── Shot_020_005/

That structure is the point. It removes ambiguity, avoids flat dumps of files, and lets supervisors and clients navigate by context instead of filenames.

The playlist name is used as the root folder, so every export stays self-contained and re-runnable.

playlist_name = playlist["name"]

We then iterate over each playlist entry and fetch the full shot record because the playlist itself does not include sequence data.

for shot in playlist["shots"]:

shot_data = gazu.shot.get_shot(shot["entity_id"])

We use the sequence name and shot name to build a deterministic directory path. This enforces a consistent playlist/sequence/shot layout on disk.

shot_name = shot_data["name"]

sequence_name = shot_data["sequence_name"]

shot_dir = os.path.join(

playlist_name,

sequence_name,

shot_name,

)

If the directory doesn't exist, we create it. This lets the script run multiple times without failing or overwriting partial downloads.

os.makedirs(shot_dir, exist_ok=True)

We can then fetch the preview file information corresponding to each shot. Typically, a picture or video:

preview = gazu.files.get_preview_file(shot["preview_file_id"])

We preserve the original filename and extension so the output matches what artists and supervisors expect to see.

preview_filename = f"{preview['original_name']}.{preview['extension']}"

preview_path = os.path.join(shot_dir, preview_filename)

We download the preview media directly into the shot folder. At this point, the playlist exists on disk as a clean, review-ready directory tree.

gazu.files.download_preview_file(preview, preview_path)

The result is a local mirror of the playlist that can be zipped, sent, archived, or reviewed without explanation.

4. Compress the Folder

Once everything is downloaded, the final step is making it easy to share. Your script should automatically compress the root playlist folder into a single archive:

import shutil

shutil.make_archive(

base_name=playlist_name,

format="zip",

root_dir=os.path.dirname(playlist_name),

base_dir=os.path.basename(playlist_name),

)

This archive becomes your handoff artifact. You can upload it to cloud storage, send it through a secure client portal, or archive it internally as a backup folder.

Clients don't worry about missing files or broken structures. They download once, unzip once, and everything just works.

Include the playlist name and date in the archive filename. Six months later, when someone asks, "Which version did we send?", you'll be glad you did.

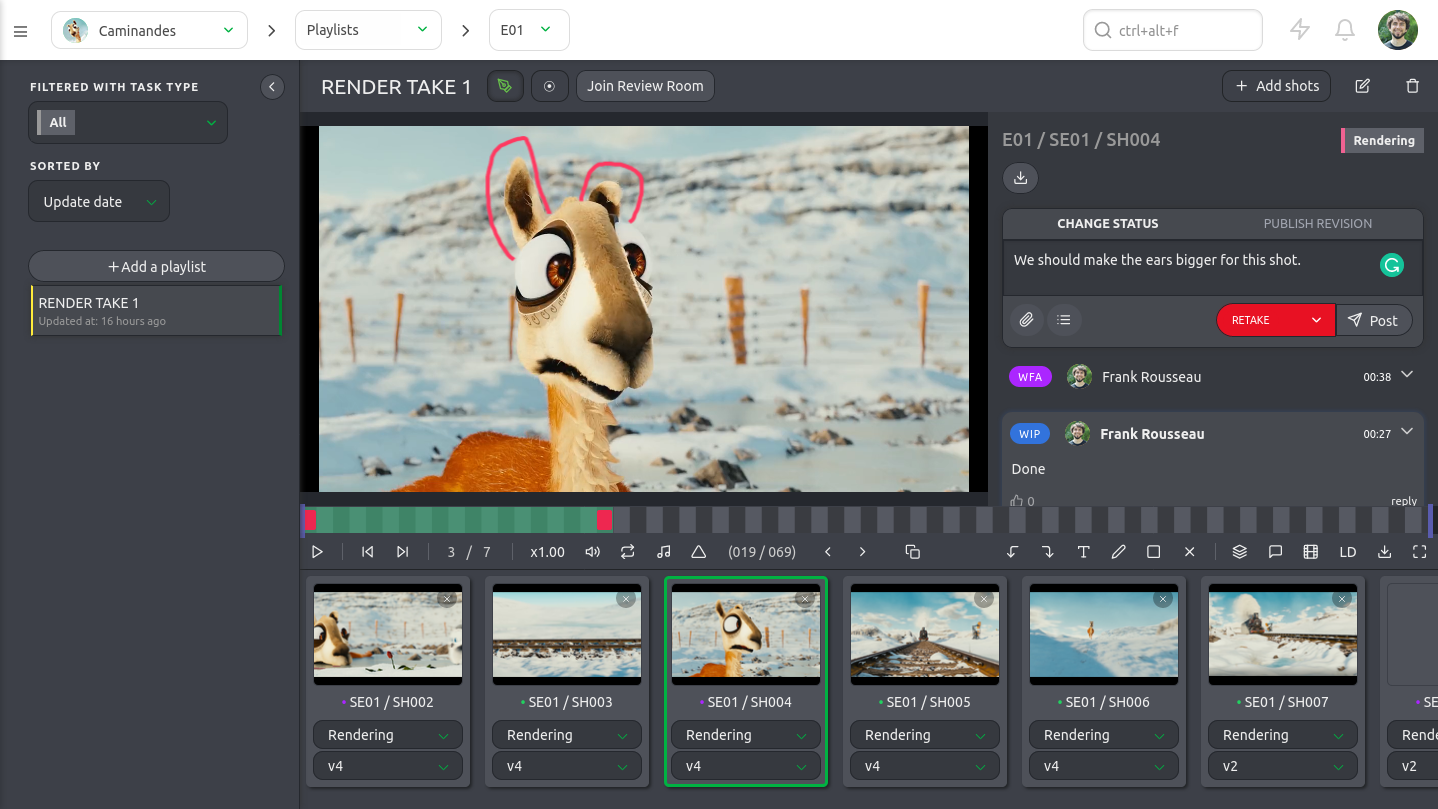

Onboard Clients In Kitsu

At some point, exporting Kitsu playlists just starts getting in the way. It’s fine when you’re sending a quick snapshot or getting a one-off note pass, but once the project goes into real iteration, things get messy fast. You’re re-exporting for every tweak, clients are commenting on outdated cuts, and feedback ends up split between emails, PDFs, and chat threads. A lot of energy goes into figuring out what the note is referring to instead of actually fixing the shot.

That’s usually when it makes sense to bring clients directly into Kitsu. They’re always looking at the current version, they can draw or comment right on the frame, and everyone sees the notes in context. Version history stays intact, so when a client asks about something “from two versions ago,” you can actually see it. For the team, it means fewer guesswork moments and less time copying notes from one place to another.

Exports are good for quick check-ins, but they don’t scale with real production. Having clients in Kitsu keeps everyone grounded in the same reality.

Conclusion

After years in animation, one lesson keeps repeating itself: the smoother your review workflow, the better your creative output. Kitsu already gives you a powerful foundation with playlists, versioning, and centralized feedback. By tapping into its data and building small automation tools, you can adapt it to almost any review scenario.

But you can also extract playlist data from Kitsu and reshape it to fit your custom review workflows. Whether you're sending offline packages, organizing assets for external partners, or just trying to make life easier for your clients, this approach puts you in control.

Check out the public Github repository to clone and modify our code to match your workflow!

And if there's one final piece of advice worth following: onboard your clients directly onto Kitsu whenever possible! Once they experience real-time review rooms, annotated notes, and version history, most never want to go back to messy email threads again.