Imagine you’re creating an animated film. 🎥 How fast could you draw one frame? 24 frames? 1,000? Even a 10-second animation can take hours, if not days, of meticulous planning to get just right. 🖌️⏳

That’s why it’s crucial to see how your ideas play out before diving into full-blown production. This is where animatics come in. 💡

In this article, we’ll explore what animatics are, their benefits, and the steps required to create one. 🚀

What's An Animatic

You're probably already familiar with storyboarding.

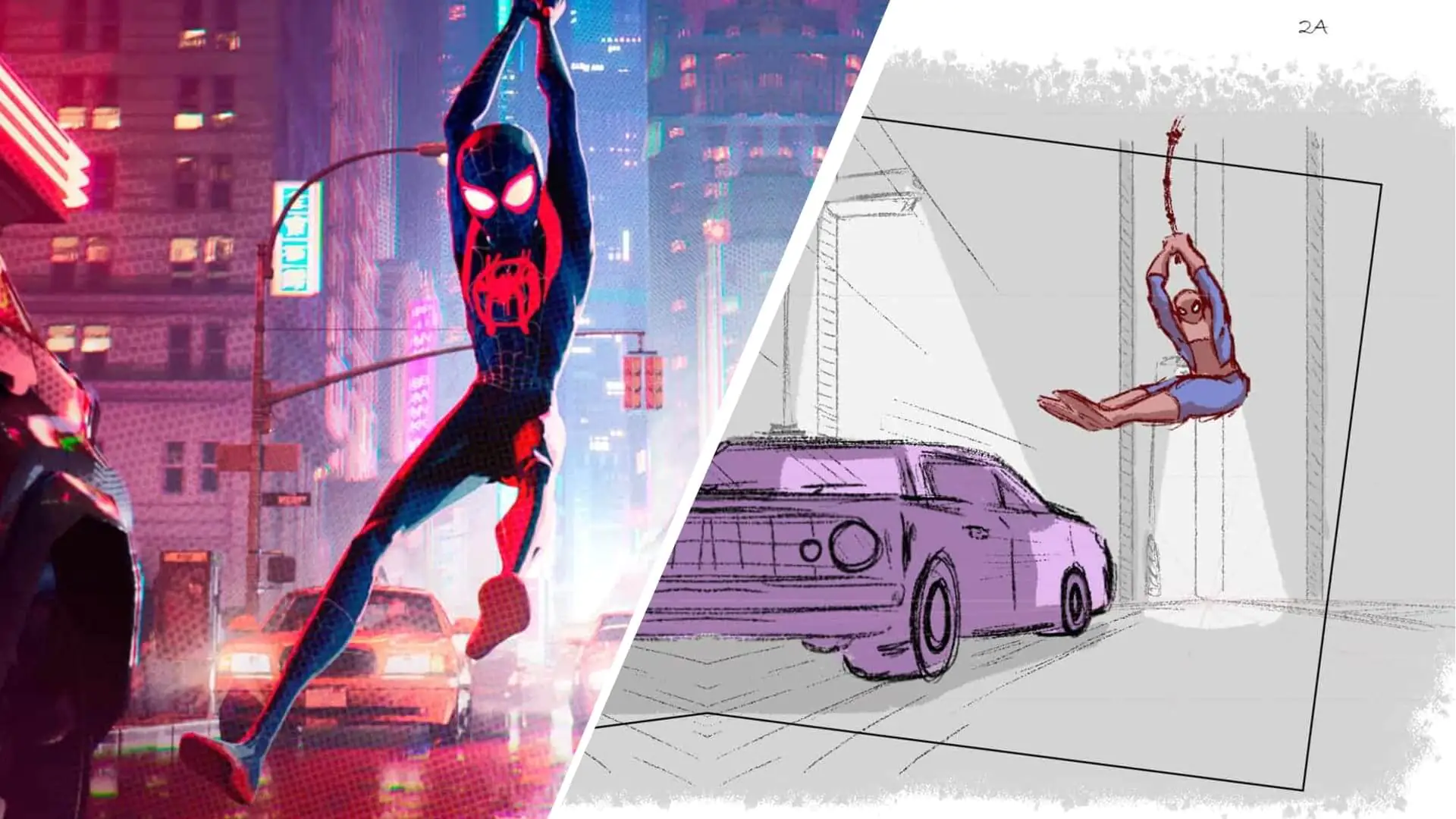

Storyboards map out the visual ideas. They are static sequences of images that outline scenes' visual structure and composition, focusing on the overall flow and critical events.

They are more straightforward and easily modified by design, typically used in early planning.

Animatics take those static images and add rough animation―timing, camera movement, and sometimes sound to create a project preview.

They bring several advantages before the production stage.

Why Use Animatics?

As previously mentioned, producing fully animated scenes is resource-intensive, so animatics save time and money by identifying potential issues regarding pacing, composition, sound design, etc., early in the process to avoid costly retakes.

It's also a precious tool for project management: animatics give a clearer sense of how long each scene will take to produce and how much it will cost, helping producers allocate resources more effectively.

Animatics serve as a communication tool for different departments involved in production (e.g., directors, animators, sound designers) because everyone can see the same rough cut and provide feedback. Likewise, test audiences or stakeholders can review animatics to gather early feedback.

The process of creating animatics involves several key steps:

1. Concept and Planning

First, animators thoroughly review the script. It's essential to finalize and thoroughly vet the script as it is the foundation for the animatic. Any inconsistencies or unresolved elements in the script lead to confusion later, so clarifying these aspects is crucial.

The script is then broken down into key scenes, shots, and sequences essential to the narrative. By outlining these elements, the animator can create an organized framework that highlights the flow and progression of the story. This breakdown determines which parts of the script to use in the animatic and how they will connect throughout the animation.

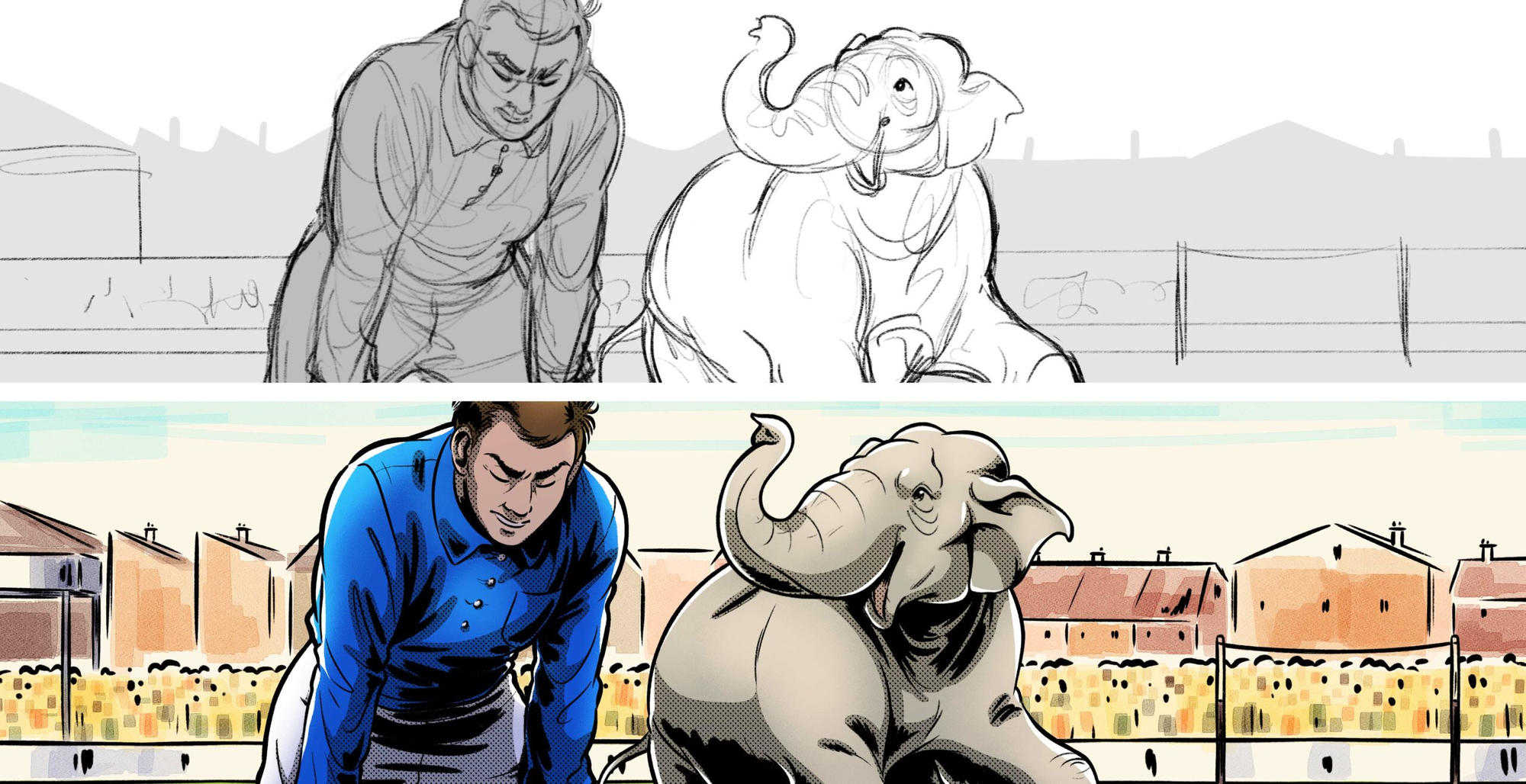

It's also important to define the visual style of the animatic: sketchy drawings, simple line art, or even more detailed designs, depending on the project's requirements or the preferences of the creative team. The chosen visual style should effectively convey the project's tone while considering the need for clarity in communication during the animatic's production.

2. Storyboarding

Storyboarding comes before creating animatics.

The first step is to draw rough, static panels that capture the essential scenes of the narrative. They can be simple but focus on conveying each scene's main actions, emotions, and transitions. Artists usually sketch out characters, backgrounds, and important props, for example.

It's important to include camera notes to guide the creation of the animatic―camera angles, zooms, pans, and movements. A storyboard isn't just a collection of drawings: it's a dynamic guide that informs how to frame and present the scenes, allowing animators to visualize the actions and how the audience will perceive those actions through the lens of a camera.

Revisions involve altering the pacing of scenes, adjusting character placements, or fine-tuning camera movements to communicate the intended story effectively.

3. Organizing the Animatic Timeline

An animatic timeline helps animators to visualize its pacing and flow.

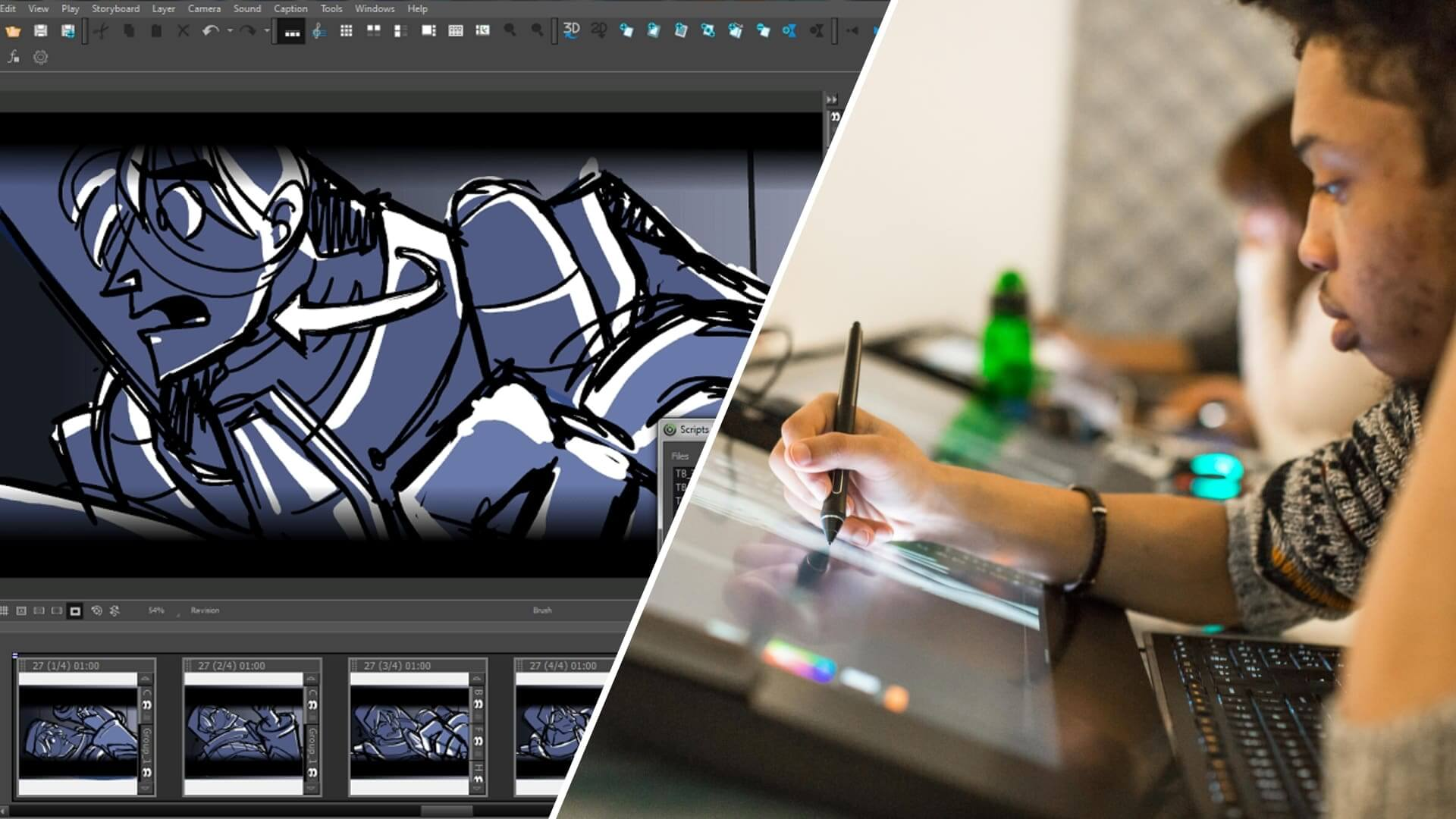

First, you transfer your storyboard frames into editing software like Adobe Premiere Pro, Adobe After Effects, or Toon Boom Harmony.

You save your storyboard frames as image files (typically in formats like JPEG or PNG) and then upload them.

The next step is to arrange them in the correct narrative order. This sequence should closely follow the script and any scene breakdowns you've created during pre-production.

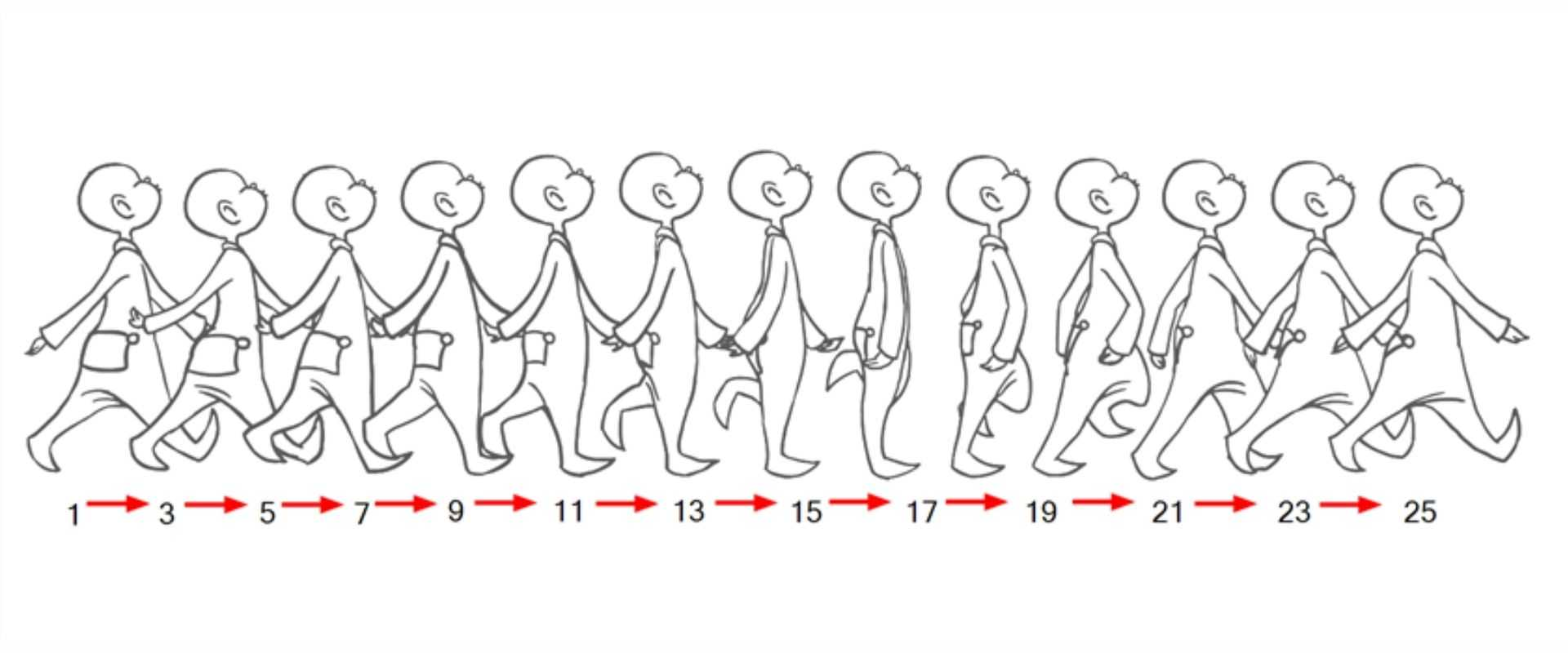

Consider how long it takes to display each storyboard frame on-screen to create an engaging animatic.

4. Rough Animation and Timing

This is where the nitty-gritty part begins.

First, you animate fundamental movements: camera actions like pans and zooms and character movements and transitions between scenes.

It'll help preview how scenes flow together.

You then experiment with the duration of each shot. Adjusting the timing of various elements is essential to maintain the narrative's pacing.

You can, for example, extend or shorten scenes to create the desired emotional impact or ensure there is enough time for dialogue to resonate: try extending a scene to build tension or shortening it to heighten excitement.

Using reference footage to get an accurate sense of timing can be incredibly helpful, especially for complex sequences.

5. Audio Integration

Audio integration enhances storytelling by conveying emotions and actions.

It's common to use a scratch track first—a temporary voiceover recorded with placeholder dialogue―to effectively sync the animated sequences with the animatic. Since the final audio may not yet be available, scratch tracks serve as a helpful reference for pacing, character interactions, and emotional beats within the storyline.

You can also incorporate rough sound effects, ambient sounds, and background music into the animatic to add depth to the visuals, allowing the creators to evaluate how sound interacts with the animated elements. For example, adding sound effects for actions like footsteps, doors closing, or environmental sounds helps establish the setting. Similarly, a preliminary music score using stock music can guide the emotional tone of the piece.

The next step is to fine-tune the timing of these audio elements to align them perfectly with the on-screen actions and visual cues. It could be changing the timing of dialogue delivery to match character mouth movements or syncing sound effects with specific moments in the animation, for example.

6. Don’t Rush Things

Even though animatics are supposed to be simple to make, you still need to consider it as an iterative process.

Begin with a rough draft. Schedule regular review sessions with cross-functional teams. Actively solicit feedback.

As you work through iterations, gradually refine keyframes and transitions.

Annotate your animatic to highlight areas that need attention or those where you have introduced significant changes.

Do not get rigidly attached to an initial idea, and be prepared to pivot: the creative vision takes precedence over everything else!

7. Final Polishing

Animators must carefully review and fine-tune not just the character movements but also the transitions between scenes and any camera movements that play a critical role in storytelling. Things like adjusting the audio levels, trimming clips for better pacing, or recording new lines if needed.

The animatic is locked in its final form, meaning no further changes are made until production begins.

This finalized version is a critical guide for the production team, making sure that everyone involved in the project has a clear vision of the story and the direction in which it is heading.

Conclusion

Animatics represent a powerful bridge between static storyboards and complete animations by incorporating rough animations, and timing and audio elements.

Creative teams can use them to pre-visualize their projects, identify potential issues, and refine elements before a more costly production phase begins.

When you present the final animatic to your team, highlight important scenes, transitions, and character movements that will be pivotal to the final product. This is when the animatic becomes the definitive blueprint for the entire production.