You want to use Flamenco, but you don't want to buy a NAS.

If you're a solo artist or a micro animation studio, that's a completely rational decision: shared storage can be expensive, adds maintenance overhead, and solves problems you may not actually have until you try to run a render farm.

Flamenco assumes a traditional studio setup: shared files, shared paths, instant access. Without a NAS, that assumption is hard to circumvent. Flamenco has no concept of production context, so it doesn't know which shot you want rendered, which version is approved, or where the job files live. And without that knowledge, it can't safely operate in a NAS-less environment.

That's where Kitsu comes in.

Kitsu already knows what Flamenco doesn't: tasks, shots, versions, approvals. By treating Kitsu as asynchronous network storage, you can move data to a Flamenco manager when it's needed, render, and avoid hard shared storage entirely.

Flamenco doesn't support this workflow out of the box. To make it work, you need to build a custom Flamenco job type that pulls context and files from Kitsu, stages them locally, and controls when and how renders run. This article shows you how to build exactly that.

You can find the complete source code for the example integration showcased in this guide on our GitHub:

🔗 https://github.com/cgwire/blog-tutorials/tree/main/flamenco-kitsu-render-farm

High-level architecture

Our setup is built around a simple idea: Flamenco does the rendering, Kitsu provides the truth.

Kitsu

↑↓ (REST API)

Custom Flamenco Job Type

├── Pre-task Python (fetch task data & files)

├── Blender render tasks (Flamenco-managed)

└── Post-task Python (upload renders back to Kitsu)

Flamenco Manager

↓

Flamenco Worker(s)

Flamenco runs exactly as intended, with a Manager scheduling work and Workers executing Blender tasks. What changes is how jobs are defined. Instead of pointing Flamenco at a shared folder and hoping every machine sees the same files, we introduce a custom Flamenco job type that understands production data and knows how to talk to Kitsu.

Kitsu sits outside the farm and exposes everything through its REST API: shots, tasks, versions, and file locations. When a render job is started—either manually or through automation—the custom job type queries Kitsu to figure out exactly what should be rendered. For example, it might ask: "Give me the latest approved lighting version for shot 020." Kitsu answers, and that answer becomes the render job.

On the Flamenco side, the Manager doesn't poll Kitsu or track production state. It simply runs the job definition it's given. The custom job type uses a small Python pre-task to fetch metadata and files from Kitsu, stage them locally in a job folder, and then hand them off to standard Blender render tasks that Flamenco already knows how to manage efficiently.

When rendering is done, a post-task Python step pushes the results back to Kitsu to upload rendered frames, create a new version, or update task status. At no point do workers need shared storage or permanent access to the same filesystem. Each worker pulls what it needs, renders locally, and pushes results back asynchronously.

1. Creating a new job type

A Flamenco job type defines how a job turns into actual work. It's the translation layer between "I want to render this" and the concrete tasks that Flamenco schedules across the farm. Conceptually, a job type declares what information it needs and how to compile that information into tasks.

At its simplest, a job type describes a label and a set of settings, then provides a function that receives those settings and builds the job. In code, it looks something like this:

const JOB_TYPE = {

label: "Kitsu Render",

settings: [

// { key: "message", type: "string", required: true },

// { key: "sleep_duration_seconds", type: "int32", default: 1 },

],

};

function compileJob(job) {

const settings = job.settings;

}

This code defines the skeleton of a custom Flamenco job type. The JOB_TYPE object declares how the job appears in Flamenco: its human-readable label and the settings it expects when a job is created.

Those settings act as typed inputs, with validation handled by Flamenco: in this example, a required string and an optional integer with a default value.

The compileJob function is where the job is turned into executable tasks; it receives the submitted job, reads the resolved settings, and would normally use them to generate render, pre-task, and post-task steps. As written, the function doesn't do any work yet, but it establishes the entry point where production logic will live.

In a real production setup, instead of a generic message, you pass in a Kitsu task ID, a shot name, the desired output location, or even the Blender version that should be used.

Where this logic lives matters. Custom Flamenco job types run on the Flamenco Manager, not on the workers. On disk, they sit alongside the manager program, for example:

$ flamenco

└── flamenco-manager

└── scripts/

└── kitsu-render.js

In practice, studios treat these job type scripts as part of their pipeline codebase. They live in version control, evolve over time, and get deployed together with Flamenco updates. That way, you can change how jobs are built and how Kitsu is queried without redeploying or reconfiguring every worker machine on the farm.

For worker scripts called by custom job types as commands, we put them next to our flamenco-worker program:

$ flamenco

└── flamenco-worker

└── kitsu-render.py

2. Adding tasks

Inside compileJob, you explicitly define the tasks that make up the job. This is where a high-level "render this shot" request turns into concrete, schedulable work that Flamenco can hand off to workers.

The example below shows the simplest possible task. An echo task is created using Flamenco's task authoring API, given a category, and then assigned a single command. That command passes the resolved job setting into the task, which will simply print the message when it runs. Finally, the task is added to the job so the Manager can schedule it.

const echoTask = author.Task("echo", "misc");

echoTask.addCommand(

author.Command("echo", {

message: settings.message,

}),

);

job.addTask(echoTask);

While this task doesn't do anything useful by itself, the pattern is the important part. The same mechanism is used to run Python scripts, launch Blender in background mode for rendering, or perform validation checks before a task is marked complete. Each task is designed to be atomic and restartable, which means if a worker crashes or a render fails at 3 a.m., Flamenco can retry just that task without derailing the entire job. That reliability is what makes this approach scale when you're running hundreds of shots overnight.

Now, let's get into the meaty part of the tutorial and code a task to download assets from Kitsu, render with Blender, and re-upload the result to Kitsu.

3. Subcommand 1: Downloading assets from Kitsu

The first real task in our Kitsu-driven job is to pull the exact data we need from Kitsu and set up a clean local workspace on the worker. Before Blender ever starts, the worker needs to know which task it's rendering and where the job files live.

Instead of writing the logic in Javascript, we use the much simpler gazu Python SDK to create a kitsu-render script, then call it in Javascript. If you don't have Python installed in your worker environment, consider creating a binary executable from the Python script.

function compileJob(job) {

const settings = job.settings;

const task = author.Task("kitsu-render", "misc");

task.addCommand(

author.Command("exec", { exe: "python3", args: ["kitsu-render.py"] }),

);

job.addTask(task);

}

The Python script authenticates against the Kitsu API, looks for TODO rendering tasks, and downloads the associated preview file containing a .blend project to render.

import os

import gazu

gazu.set_host("http://localhost/api")

user = gazu.log_in("admin@example.com", "mysecretpassword")

projects = gazu.project.all_projects()

project = projects[0]

tasks = gazu.task.all_tasks_for_project(project)

rendering = gazu.task.get_task_type_by_name("Rendering")

todo = gazu.task.get_task_status_by_name("todo")

render_tasks = [

t

for t in tasks

if t["task_type_id"] == rendering["id"] and t["task_status_id"] == todo["id"]

]

for task in render_tasks:

files = gazu.files.get_all_preview_files_for_task(task)

if not files:

continue

latest = files[-1]

if latest["extension"] == "blend":

task_to_render = task

latest_blend = latest

break

if task_to_render is None:

raise RuntimeError("No render task with a .blend preview found")

target_path = os.path.join(

"/tmp", latest_blend["original_name"] + "." + latest_blend["extension"]

)

gazu.files.download_preview_file(latest_blend, target_path)

This step is what makes a NAS-less workflow viable. Each worker pulls only the files it needs for the specific task it's running, instead of mounting or syncing an entire production tree. If the download fails, Flamenco can retry the task automatically without human intervention.

4. Subcommand 2: Blender render

Once the blend file to render is staged locally on the worker, we can render it programmatically with the bpy library:

bpy.ops.wm.open_mainfile(filepath=target_path)

output_path = os.path.join(

"/tmp", latest_blend["name"] + ".mp4"

)

bpy.context.scene.render.image_settings.file_format = "FFMPEG"

bpy.context.scene.render.ffmpeg.format = "MPEG4"

bpy.context.scene.render.ffmpeg.codec = "H264"

bpy.context.scene.render.ffmpeg.constant_rate_factor = "HIGH"

bpy.context.scene.render.ffmpeg.gopsize = 12

bpy.context.scene.render.ffmpeg.audio_codec = "AAC"

bpy.context.scene.render.filepath = output_path

bpy.ops.render.render(animation=True)

A more advanced pipeline would leverage Flamenco's native 'blender-render' command to automatically split the frame range into smaller units of work and distribute them across available workers. If a machine drops out or a frame fails, only those frames are retried, so there's no need to restart the entire shot or build custom queue logic to handle parallelism.

But to keep our example simple, we just render the whole video in one worker.

5. Subcommand 3: Uploading results back to Kitsu

The final step in the job is a post-render subcommand that pushes the render results back to Kitsu. At this point, the worker has finished its frame range locally, and the farm's responsibility shifts from computation to publishing. This is where rendered output becomes visible to the rest of the production.

The example below shows a minimal Python instruction that uploads the resulting video file to Kitsu as an attachment on the original task.

result = gazu.task.publish_preview(

task_to_render,

todo,

comment="rendered",

preview_file_path=output_path,

)

In a real production pipeline, this step usually does more than just upload files. We can create a new version in Kitsu, update the task status to something like Done, and trigger review or notification workflows so supervisors know new output is ready. Because this logic is just Python running inside a Flamenco task, it's easy to evolve as production needs change without touching the render farm itself.

6. Triggering the workflow

Once the custom job type is in place, the workflow is triggered by submitting a job request to the Flamenco Manager. During development, this is often done manually by calling the Manager's REST API directly. It's a fast way to validate that job compilation works, settings are wired correctly, and tasks behave as expected before any automation is layered on top.

The example below submits a job of type kitsu-render to the Manager. Along with basic metadata for tracking and attribution, the request includes a priority value and an empty settings object, which would normally carry production-specific inputs like a Kitsu production ID. When the job is accepted, the Manager invokes the custom job type, compiles tasks, and schedules them across available workers.

curl -X 'POST' \

'http://172.17.0.1:8080/api/v3/jobs' \

-H 'accept: application/json' \

-H 'Content-Type: application/json' \

-d '{

"metadata": {

"project": "kitsu",

"user.email": "basunako@gmail.com",

"user.name": "kitsu"

},

"name": "Kitsu Render",

"priority": 50,

"settings": {},

"submitter_platform": "linux",

"type": "kitsu-render"

}'

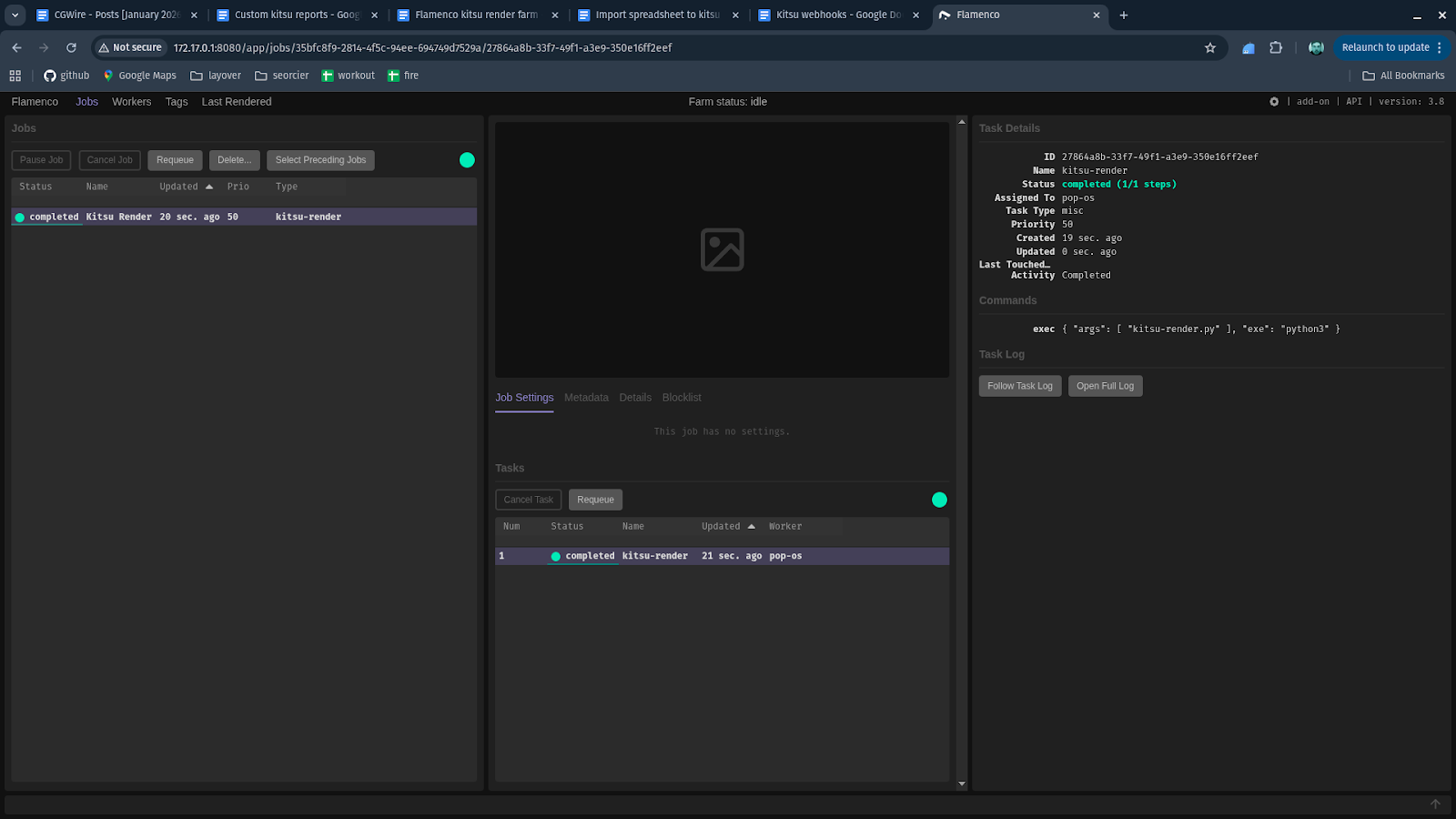

We can see the manager received the job request and assigned it to a worker:

This manual trigger is primarily a development tool. It lets you iterate on job logic, test edge cases, and rerun jobs without involving artists or production tools.

In production, studios always automate this step. A small service (often a cron job or lightweight webhook listener) periodically queries Kitsu for tasks that are ready to render, like shots that were just approved or published. When it finds one, it submits a corresponding job to the Flamenco Manager using the same API call.

With this in place, Flamenco becomes a production-aware render backend instead of waiting for humans to push buttons, reacting automatically to changes in Kitsu and keeping the farm in sync with the state of the production.

Conclusion

What you've built in this article is a fundamentally different way to think about rendering in small studios.

By using a custom Flamenco job type to pull context and data from Kitsu, stage work locally, render through Flamenco's native scheduler, and push results back asynchronously, you've removed the need for shared storage without sacrificing reliability or scale.

Each piece has a clear responsibility: Kitsu defines what is true in production, Flamenco decides how work runs, and your custom job type is the glue that keeps them in sync. That separation is what makes the system resilient, debuggable, and adaptable as your pipeline grows.

Understanding this pattern is important because it lets you build render infrastructure that matches the reality of solo artists and micro-studios.

But don't just leave here, clone our example Github repository for this article and start rendering today!